In the relentless pursuit of sustainable water solutions, scientists are increasingly turning to nature's master engineers for inspiration. A recent breakthrough, emerging from the intricate world of desert-dwelling beetles, has sent ripples through the fields of materials science and engineering. Researchers have successfully decoded and replicated the multi-stage, hierarchical surface structures that certain Namib Desert beetles use to harvest water from the air, achieving a staggering leap in condensation efficiency that promises to redefine the technology of atmospheric water generation.

The story begins in one of the most arid environments on Earth. For the Stenocara gracilipes and other tenebrionid beetles, survival hinges on an extraordinary ability to collect microscopic water droplets from early morning fog. For decades, the prevailing understanding was that this was a simple two-step process: hydrophilic bumps to nucleate water droplets, surrounded by waxy, hydrophobic channels to guide the collected water toward the beetle's mouth. This biomimetic principle led to the development of various fog-harvesting meshes and surfaces. However, a new, more detailed investigation has revealed that this model is a dramatic oversimplification of a far more sophisticated system.

Using advanced high-resolution imaging techniques like scanning electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy, an international research team has uncovered a complex, multi-tiered architecture on the beetle's elytra (wing cases). The surface is not merely a collection of bumps and valleys. Instead, it features a hierarchical landscape with nanostructures atop microstructures, each level playing a distinct and synergistic role in the water capture and transport process. The very top of the bumps are covered in a forest of nanoscopic pillars, which drastically increase the surface area and serve as ultra-efficient nucleation sites. This nano-texturing allows droplets to form at a lower critical saturation threshold, meaning condensation begins earlier and more readily than on any human-made smooth or simply micro-textured surface.

Beneath this nano-layer lies the microstructure of the bumps themselves. Their specific shape and curvature are critical for the next phase. As the nanoscopic droplets coalesce into larger micro-droplets, the geometry of the bumps generates a subtle pressure gradient. This isn't a passive roll-off; it's an active directional push. The curvature is designed to destabilize the droplet's adhesion at a precise size, initiating a rapid transfer downward. This is where the previous model fell short. The channels below are not merely waxy and slippery. They are themselves micro-grooved, acting like miniature aqueducts. A combination of capillary action and surface tension gradients within these grooves propels the water with remarkable speed and efficiency toward the beetle's waiting mouth, preventing any loss from evaporation or misdirection.

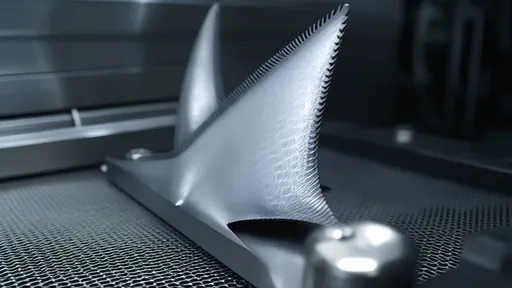

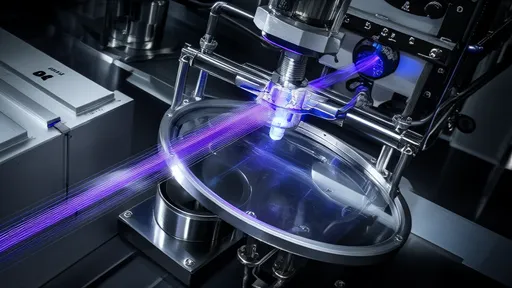

The true breakthrough came when the research team moved from observation to replication. By employing multi-material 3D nano-printing and other advanced fabrication methods, they created a synthetic surface that mimicked this exact multi-level hierarchy. The results were nothing short of revolutionary. In controlled humidity chambers, the bio-inspired surface demonstrated a condensation efficiency over 150% higher than the best existing fog-harvesting designs and a staggering 500% improvement over conventional condenser plates used in atmospheric water generators. The synthetic surface not only collected more water but did so faster and with significantly less energy input, as it relied on its physical structure rather than external energy for droplet movement.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond a scientific curiosity. In a world grappling with water scarcity, the potential applications are vast and urgent. Imagine next-generation atmospheric water generators—the units that pull drinking water from humid air—that are smaller, more efficient, and capable of operating in a wider range of climates, including drier regions previously thought unsuitable. These devices could become viable off-grid solutions for remote communities. Furthermore, this technology could revolutionize the efficiency of industrial condensation processes, such as those in power plants and HVAC systems, leading to massive reductions in energy consumption and water waste. Even the field of lab-on-a-chip diagnostics could benefit, with precise micro-fluidic control being managed by these intricate, self-propelling surface patterns.

This research elegantly demonstrates that sometimes, the most advanced solutions are not born in a sterile lab but have been evolving in plain sight for millions of years. The humble desert beetle, a survivor of extreme austerity, has offered up a masterclass in sustainable water collection. By looking deeper and understanding the nuanced, hierarchical architecture of its shell, scientists have not only unlocked a new secret of biology but have also paved the way for a new era of high-efficiency condensation technology. This is a powerful testament to the potential of biomimicry, proving that the next wave of human innovation may well be written in the language of nature.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025