In the intricate dance of evolution, nature has crafted some of the most sophisticated sensory systems known to science. Among these, the compound eyes of insects stand as marvels of biological engineering, offering a panoramic and highly efficient method of perceiving the world. Unlike the single-lens eyes of vertebrates, compound eyes consist of thousands of individual optical units called ommatidia, each functioning as a separate visual receptor. This structure not only provides an exceptionally wide field of view but also enables rapid motion detection and superior performance in low-light conditions. Inspired by this natural design, researchers and engineers are pioneering a new frontier in imaging technology: panoramic detection systems based on the principles of insect vision. These bio-inspired systems are poised to revolutionize fields ranging from robotics and surveillance to medical imaging and autonomous vehicles, offering capabilities that traditional cameras cannot match.

The fundamental brilliance of insect vision lies in its compound architecture. Each ommatidium is a self-contained unit with its own cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells, working in concert to capture a small portion of the visual field. The brain then integrates these myriad inputs into a cohesive image, much like a mosaic. This design allows insects to detect movement with astonishing speed—a necessity for evading predators or capturing prey. For instance, a housefly can process visual information up to seven times faster than a human, making it nearly impossible to swat. Moreover, the hemispherical arrangement of ommatidia grants insects an almost 360-degree field of view, eliminating blind spots and providing constant environmental awareness. These attributes have not escaped the notice of scientists seeking to overcome the limitations of conventional imaging systems, which often struggle with narrow fields of view, motion blur, and poor performance in dynamic lighting conditions.

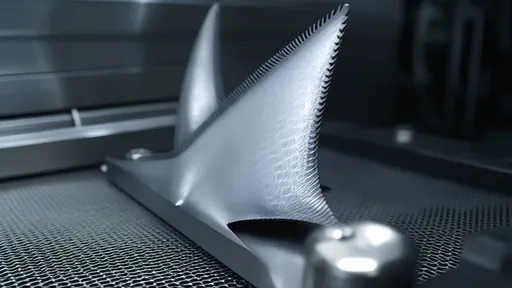

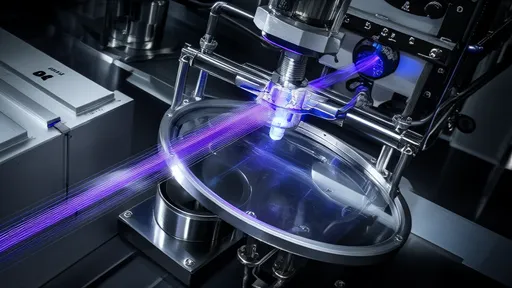

Translating biological principles into technological innovation is no small feat, yet recent advancements in microfabrication, optics, and computational algorithms have made it increasingly feasible. Early attempts to replicate compound eyes involved assembling arrays of microlenses on curved surfaces, mimicking the hemispherical layout of natural ommatidia. However, these prototypes were often hampered by manufacturing challenges and optical imperfections. Breakthroughs in materials science, such as the development of flexible, stretchable electronics, have enabled the creation of more sophisticated and durable artificial compound eyes. For example, researchers have successfully fabricated elastomeric microlens arrays that can be deformed into curved shapes without losing optical clarity. Coupled with advanced image processing software that mimics neural integration, these systems can stitch together inputs from thousands of lenses in real-time, producing high-resolution panoramic images with minimal distortion.

The applications of insect-inspired panoramic detection technology are as diverse as they are transformative. In robotics, equipping autonomous machines with wide-angle vision enhances their ability to navigate complex environments without collisions. Search and rescue robots, for instance, can benefit from 360-degree awareness in disaster zones where every second counts. Similarly, in the automotive industry, panoramic imaging could significantly improve the safety of self-driving cars by providing a comprehensive view of surroundings, detecting pedestrians, cyclists, and obstacles from all angles. Surveillance systems armed with such technology offer unparalleled monitoring capabilities, covering large areas with fewer devices and reducing blind spots. Even in medicine, endoscopic capsules with compound eye-inspired cameras could traverse the gastrointestinal tract, capturing panoramic views to aid in diagnosis and reduce invasive procedures.

Despite the promising advancements, several hurdles remain on the path to widespread adoption. One significant challenge is scaling up production while maintaining precision and affordability. Manufacturing thousands of microscopic lenses on a curved surface requires nanoscale accuracy, which can be costly and time-consuming. Additionally, processing the vast amount of data generated by these systems demands substantial computational power and efficient algorithms to avoid latency issues. Energy consumption is another concern, particularly for portable or battery-operated devices. Researchers are exploring solutions such as neuromorphic computing, which mimics the brain's efficient processing, and novel materials that reduce the need for complex electronics. As these technologies mature, we can expect artificial compound eyes to become more accessible and integrated into everyday applications.

Looking ahead, the future of insect-inspired imaging systems is brimming with potential. Emerging trends point toward hybrid designs that combine the strengths of compound eyes with other biological features, such as the polarization sensitivity of mantis shrimp or the night vision of moths. Such integrations could lead to multispectral imaging systems capable of perceiving beyond the visible light spectrum. Moreover, as artificial intelligence continues to evolve, so too will the ability of these systems to learn and adapt to their environments, much like their biological counterparts. The convergence of biology and technology—often termed biomimicry—is not merely about imitation but about drawing inspiration from millions of years of evolutionary refinement to solve modern problems. In this light, the humble insect eye is more than a biological curiosity; it is a blueprint for the next generation of visual technology.

In conclusion, the development of panoramic detection systems inspired by insect vision represents a thrilling intersection of biology and engineering. By harnessing the principles of compound eyes, researchers are overcoming the limitations of traditional imaging and opening new possibilities across numerous industries. While challenges in manufacturing and processing persist, ongoing innovations promise to make these systems more efficient, affordable, and versatile. As we continue to learn from nature's designs, we move closer to creating technologies that are not only advanced but also inherently harmonious with the world around us. The journey from fly to future is well underway, and the view, quite literally, has never been broader.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025