In the relentless pursuit of efficiency within the renewable energy sector, a quiet revolution is underway, inspired not by complex machinery but by the ancient, streamlined forms of ocean predators. The application of shark skin biomimicry, specifically its unique drag-reducing properties, to wind turbine blades represents a frontier of aerodynamic innovation with the potential to significantly boost power output and operational longevity.

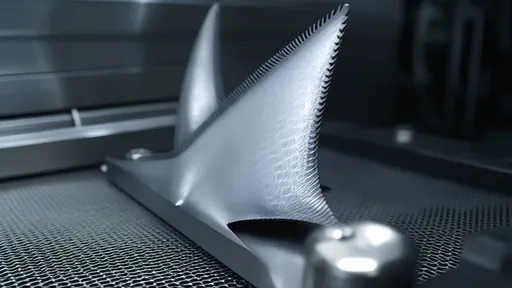

The genesis of this technology lies in the remarkable hydrodynamics of shark skin. Unlike the smooth surfaces engineered by humans for reduced resistance, shark skin is covered in millions of microscopic, tooth-like structures called dermal denticles. These tiny ridges are meticulously arranged in patterns that manipulate the flow of water over the shark's body. They reduce drag by managing the behavior of the boundary layer—the thin layer of fluid immediately adjacent to the surface. By minimizing turbulent flow and encouraging laminar (smooth) flow over a greater portion of the body, these denticles allow sharks to move through water with breathtaking efficiency and silence, a trait honed over millions of years of evolution.

For decades, engineers and scientists have sought to replicate this natural phenomenon in artificial surfaces, a field known as riblet technology. The principle is deceptively simple: microscopic streamwise grooves on a surface can inhibit the cross-flow of fluid particles in the boundary layer, thereby dampening the formation and growth of turbulent vortices. This translates directly to a reduction in skin friction drag, which is a dominant source of resistance for bodies moving through any fluid, be it water or air. The challenge has always been in designing, manufacturing, and applying these microstructures at a scale and consistency that is both effective and economically viable for large-scale industrial applications.

The wind energy industry presents a perfect use case for this biomimetic technology. Wind turbine blades are colossal structures, often exceeding the length of a commercial aircraft wing, and their aerodynamic performance is the single most critical factor in determining a turbine's efficiency and power generation capacity. As air flows over the surface of a blade, a boundary layer forms. At lower wind speeds, this flow remains largely laminar, but as speed increases, it inevitably separates and becomes turbulent, creating a large region of low-pressure drag behind the blade known as a wake. This drag forces the turbine to work harder, extracting less energy from the wind and subjecting the entire structure to increased vibrational stresses that accelerate material fatigue.

By applying a surface coating or manufacturing the blade with integrated riblet structures mimicking shark denticles, engineers can effectively manage this airflow. The micro-grooves act to keep the boundary layer attached to the blade surface for a longer distance, delaying the onset of flow separation and shrinking the size of the turbulent wake. The result is a dual benefit: a significant reduction in drag and a simultaneous increase in lift. For a wind turbine, this means the blades can capture more energy from the same wind speed, begin operating efficiently at lower cut-in wind speeds, and experience reduced structural loads. The cumulative effect is a substantial boost in annual energy production (AEP) and an extension in the operational lifespan of the turbine.

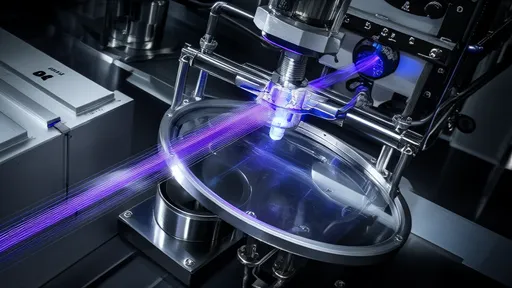

The journey from biological observation to industrial application is fraught with engineering challenges. The optimal size, shape, and spacing of the riblets are not universal; they must be meticulously calculated based on the specific aerodynamic profile of the blade and the expected range of wind speeds it will encounter. Furthermore, applying a delicate micro-structured surface to a massive blade that must withstand decades of punishment from rain, hail, UV radiation, and extreme temperature fluctuations is a monumental task. The coating must be incredibly durable, resistant to erosion, and easy to maintain or repair. Advances in composite materials science and precision manufacturing, such as advanced molding techniques and laser etching, are now making it possible to create these surfaces with the required robustness and precision.

Early field tests and commercial pilot programs have yielded highly promising results. Turbines equipped with biomimetic blade surfaces have demonstrated measurable improvements in performance. Data collected from these installations often shows an increase in AEP of several percentage points. While a single-digit percentage might seem modest, for a multi-megawatt turbine operating over a 20-year lifespan, it translates to a massive amount of additional clean energy generated and a significant improvement in the project's economic return on investment. This makes the technology not just an engineering curiosity, but a commercially attractive upgrade for both new turbine installations and the retrofitting of existing fleets.

Looking forward, the integration of shark skin technology is poised to become a more standard feature in blade design. Research is ongoing to develop adaptive or smart riblet surfaces that could change their geometry in response to changing wind conditions to maintain optimal performance. Furthermore, the principles of biomimicry are being expanded beyond drag reduction. Scientists are looking at the silent flight of owls to design quieter turbine blades and studying the self-healing properties of various biological materials to create blades that can repair minor surface damage autonomously.

The adoption of nature's blueprint for fluid dynamics is a powerful testament to the potential of biomimicry. In the quest for a sustainable energy future, solutions are not always found by looking forward into increasingly complex computer models, but sometimes by looking back at the unparalleled engineering perfected by evolution. The humble shark, a master of efficiency for over 400 million years, is now guiding the hand of human innovation, helping to harness the wind more effectively and propel the world toward a cleaner, more efficient energy paradigm.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025