In the relentless pursuit of mitigating anthropogenic climate change, the scientific community is increasingly turning its gaze beneath our feet, to the very bedrock of the planet. Among the most promising and geologically elegant solutions is the concept of mineral carbonation, specifically utilizing the abundant and reactive volcanic rock, basalt. This process, which mimics and accelerates Earth's natural carbon sequestration methods over millennia, offers a tangible pathway to permanently lock away vast quantities of carbon dioxide. The design of geological reactors for the carbon mineralization of CO₂ within basaltic formations is not merely an engineering challenge; it represents a fundamental reimagining of waste management on a planetary scale, transforming a harmful greenhouse gas into a stable, benign carbonate mineral.

The underlying principle is as simple as it is powerful. When carbon dioxide comes into contact with certain silicate minerals rich in calcium, magnesium, and iron—constituents abundantly found in basalt—a chemical reaction is initiated. This reaction, over time, converts the gaseous CO₂ into solid carbonate minerals like calcite, magnesite, or siderite. This is the Earth's own long-term carbon cycle at work. The challenge, and the core of modern reactor design, is to engineer conditions that accelerate this natural process from geological timescales to a timeframe relevant for human climate goals, ideally on the order of years or decades.

Basalt is the ideal candidate for this endeavor for several compelling reasons. It is one of the most common rock types on Earth, forming the bedrock of the entire ocean floor and large continental regions known as Large Igneous Provinces, such as the Deccan Traps in India or the Columbia River Basalt Group in the United States. Its mineralogy, particularly the presence of reactive minerals like olivine, pyroxene, and plagioclase feldspar, provides the necessary chemical components for carbonation. Furthermore, basalt formations are often characterized by fractured and porous structures, offering immense surface area for reactions and natural pathways for fluid injection and migration.

The design of an effective geological reactor hinges on creating and managing a triumvirate of critical factors: the reactivity of the host rock, the accessibility of its surface area, and the precise control of in-situ conditions. Unlike a conventional surface factory, this reactor is the subsurface formation itself. Engineers and geoscientists must first meticulously characterize a potential site through seismic imaging, core sampling, and hydrological studies to map its porosity, permeability, and mineral composition. This initial assessment determines the feasibility of transforming a specific basalt formation into an efficient carbon mineralization plant.

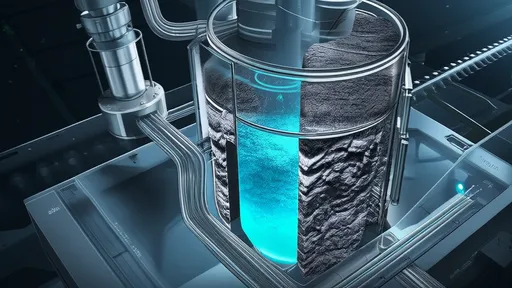

Injection strategy forms the backbone of the reactor's operation. The most common approach involves drilling injection wells into the target basalt formation, typically located anywhere from 500 to 2000 meters below the surface. At these depths, the combination of pressure and temperature creates conditions where CO₂ behaves as a supercritical fluid—a state that possesses the density of a liquid but the viscosity and diffusivity of a gas. This supercritical CO₂ is then injected into the formation. However, a more promising method involves dissolving the captured CO₂ into large volumes of water, creating carbonated water, which is then injected. This aqueous solution greatly enhances the contact between CO₂ and the mineral surfaces, dramatically accelerating the reaction rates.

Once injected, the real chemistry begins. The carbonated fluid, slightly acidic, percolates through the network of fractures and pores in the basalt. It begins to dissolve the primary silicate minerals, releasing divalent cations like Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Fe²⁺ into the solution. This is the rate-limiting step in the natural process. The engineered reactor seeks to optimize this dissolution. Subsequently, these liberated cations react with the dissolved bicarbonate ions (HCO₃⁻) in the fluid to precipitate out as solid carbonate minerals. These newly formed crystals grow within the pores and fractures, effectively locking the carbon away in a thermodynamically stable form for millions of years.

Monitoring and verification are paramount to ensuring the integrity and efficiency of the geological reactor. A suite of sophisticated tools is deployed to track the CO₂ plume, measure reaction progress, and confirm permanent mineralization. Tracers, chemical and isotopic, can be injected with the CO₂ to follow its path underground. Repeated seismic surveys can image the subsurface, showing how the plume evolves over time. Most definitively, fluid samples drawn from monitoring wells can be analyzed for changes in chemistry—a decrease in dissolved CO₂ and an increase in bicarbonate and carbonate ions, coupled with the presence of the key cations, provides direct evidence that mineralization is actively occurring.

The advantages of this technology are profound. The storage security is unparalleled; unlike saline aquifer storage where CO₂ remains in a buoyant supercritical state, requiring careful site management to prevent leakage, mineralized carbon is solid and immobile. The capacity is enormous; global basalt formations have the theoretical potential to store centuries worth of anthropogenic CO₂ emissions. Furthermore, the process itself is exothermic, producing heat as a byproduct, which could potentially be harnessed. There are also minimal long-term monitoring liabilities once mineralization is confirmed, as the risk of leakage is effectively eliminated.

However, the path forward is not without its significant hurdles. The large water footprint required for the aqueous injection method raises concerns, particularly in water-scarce regions, necessitating research into using non-potable saline water or wastewater. The energy costs associated with capturing, compressing, transporting, and injecting the CO₂ remain substantial, though these are challenges shared by all Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies. Public perception and robust regulatory frameworks also need to evolve to govern this new form of subsurface activity and ensure its safe and equitable implementation.

Pilot projects around the world have already moved this concept from theory to tangible reality. The CarbFix project in Iceland has successfully demonstrated the rapid mineralization of injected CO₂ in basaltic rocks, achieving over 95% conversion to solid carbonate in less than two years—a stunning acceleration of a natural process. Similarly, the Wallula Basalt Pilot project in Washington State, USA, has provided further proof-of-concept, confirming mineralization through detailed wellbore sampling. These successes are beacon lights, guiding the way toward larger-scale commercial deployment.

In conclusion, the design of geological reactors for玄武岩 (basalt) carbon sequestration through mineralization stands as a testament to innovative climate engineering. It is a solution that works with Earth's geology, not against it. By cleverly engineering subsurface conditions to stimulate a natural process, we can transform the primary driver of global warming into a harmless rock, effectively turning a liability into a part of the landscape. As research progresses and pilot projects scale up, this technology promises to be a cornerstone of a diversified and permanent strategy to restore balance to Earth's carbon cycle and secure a stable climate for future generations.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025