The stark white expanse of glaciers, long perceived as eternal and unchanging, is now one of the most visible and alarming casualties of a warming planet. These colossal rivers of ice, which hold the majority of the world's freshwater, are not merely scenic wonders; they are critical climate regulators, vital freshwater reservoirs, and stabilizers of global sea levels. Their accelerating retreat, driven by rising atmospheric and oceanic temperatures, signals a profound shift in Earth's ecological balance. The loss of glacial mass contributes directly to sea-level rise, threatens the water security of millions, and disrupts regional climates. In the face of such a monumental challenge, conventional mitigation strategies often feel insufficient, prompting scientists and engineers to explore innovative, direct intervention technologies. Among the most promising and debated of these frontier solutions is the application of high-albedo nanocoating materials directly onto vulnerable ice surfaces.

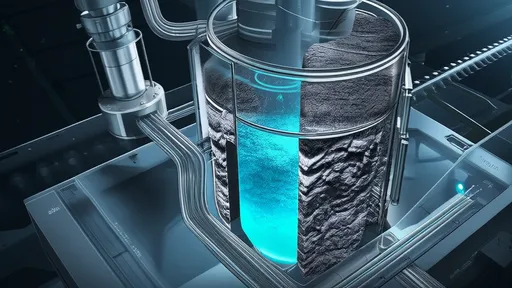

The core scientific principle behind this technology is elegantly simple: albedo, or surface reflectivity. A pristine, snow-covered glacier has a very high albedo, meaning it reflects a significant portion of incoming solar radiation back into space, thus remaining cool. However, as a glacier melts, its surface darkens due to the exposure of older, dirtier ice and the accumulation of light-absorbing particles like dust and soot. This darker surface absorbs more solar energy, accelerating the melt in a vicious feedback loop known as the ice-albedo feedback effect. The goal of high-reflectivity nanocoatings is to artificially break this cycle. By applying a thin, protective layer of highly reflective material, researchers aim to restore a high-albedo state to the ice, effectively shielding it from a portion of the sun's radiative energy and slowing the rate of ablation.

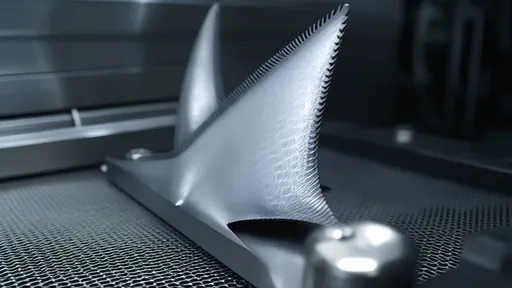

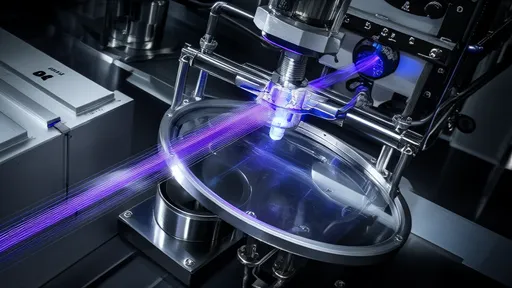

The magic of this approach lies in the nano-scale engineering of the coating materials. These are not simple white paints. Scientists are developing advanced composites often based on natural minerals like feldspar or specially engineered silicon dioxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. The size, shape, and distribution of these particles are meticulously calibrated to maximize the scattering of sunlight across a wide spectrum, particularly in the visible and near-infrared ranges where a significant amount of solar energy is transmitted. Some formulations are designed to be superhydrophobic, causing water to bead up and roll off, which helps prevent the coating from being washed away by meltwater and maintains its reflective integrity over time. The ideal nanocoating is a multifaceted product: incredibly reflective, environmentally benign, durable enough to withstand harsh glacial conditions, and ultimately biodegradable or designed to safely diminish after fulfilling its protective role.

Field testing, though still in its relative infancy, has yielded cautiously optimistic results. Pilot projects have been conducted on smaller, often more accessible glaciers in the Alps, the Andes, and other mountain ranges. In one notable Swiss study, a biodegradable reflective powder based on calcium carbonate was spread over a section of the Morteratsch glacier. Over the subsequent summer months, researchers recorded a measurable reduction in ice melt on the treated area compared to adjacent untreated control sections. The coating successfully increased the surface albedo, effectively creating a protective shield that preserved several feet of ice thickness that would have otherwise been lost. Similar small-scale trials in Italy and Chile have supported these findings, demonstrating that the technical concept is sound and can produce a tangible, localised preservation effect under real-world conditions.

Despite its promising potential, the large-scale deployment of ice-protective nanocoatings is fraught with complex challenges and spirited debate. The most immediate hurdle is logistical. Glaciers are vast, remote, and treacherous environments. Coating square kilometres of uneven, crevassed terrain using aircraft or ground teams presents a monumental engineering and operational challenge, with significant associated costs and energy consumption. The long-term environmental impact is perhaps the most critical concern. While materials are designed to be non-toxic, their interaction with delicate glacial ecosystems—including unique microbes and the downstream watersheds—is not fully understood. Introducing any foreign substance, no matter how benign, into a pristine environment carries inherent risks that must be rigorously assessed.

Furthermore, the technique sparks important philosophical and ethical questions. Critics argue that it is a form of geoengineering—a technological fix that addresses a symptom (ice melt) rather than the root cause (greenhouse gas emissions). There is a palpable fear that such innovations could create a moral hazard, providing a false sense of security and potentially diverting political and financial capital away from the essential work of emissions reduction. Proponents counter that we have entered an era of climate crisis where a multi-pronged strategy is necessary. They frame nanocoating not as a replacement for decarbonization, but as a targeted, temporary defense mechanism—a "buying time" intervention to protect the most vulnerable and critical glaciers, such as those preventing catastrophic sea-level rise or safeguarding community water supplies, while the world transitions to a low-carbon economy.

The future trajectory of glacial nanocoating technology will depend on a confluence of factors. Continued research is paramount to develop next-generation materials that are more effective, longer-lasting, and completely environmentally safe. Lifecycle analyses must be conducted to ensure the process of manufacturing and applying the coating does not create a larger carbon footprint than the ice it saves. Crucially, this technology cannot be developed in a vacuum. Its potential deployment must be guided by robust international governance, transparent scientific assessment, and, most importantly, the free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous and local communities who are the guardians of these frozen landscapes and who will be most directly affected by such interventions.

In conclusion, high-reflectivity nanocoating for glacier protection represents a fascinating and controversial frontier in humanity's response to climate change. It is a testament to human ingenuity, born from a desperate need to preserve our planet's icy sentinels. The technology holds the promise of acting as a localized buffer against warming, offering a chance to safeguard vital ecosystems and water resources. However, it is not a silver bullet. It is a complex tool, laden with significant ethical, environmental, and practical considerations. Its ultimate value and appropriateness will be determined not just by its scientific efficacy, but by the wisdom with which we choose to use it—or not use it—as part of a much broader, unwavering commitment to solving the climate crisis at its source.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025