In the quiet hum of biotechnology laboratories, a material once reserved for luxury textiles is being rewoven into the future of medicine. Spider silk, long admired for its unparalleled strength and elasticity, has historically been an impractical resource for widespread medical use due to spiders' cannibalistic and solitary nature. However, a groundbreaking solution has emerged from an ancient collaborator: the silkworm. Through genetic engineering, scientists have successfully implanted spider silk protein genes into silkworms, creating a hybrid material often referred to as transgenic silkworm silk or recombinant spider silk. This innovation is not merely a scientific curiosity; it is paving the way for a new era in medical materials, offering solutions that are both biologically compatible and remarkably robust.

The journey to this achievement was fraught with challenges. Spider silk proteins, known as spidroins, are large and complex, making their synthesis in foreign hosts difficult. Early attempts to produce them in bacteria, yeast, or even goat's milk yielded only small quantities or shorter, less functional proteins. The silkworm, Bombyx mori, emerged as an ideal candidate because it naturally produces large amounts of silk protein and its genetics are well-understood. By using advanced gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9, researchers have been able to insert spider silk DNA sequences into the silkworm genome, effectively turning these insects into tiny, efficient bioreactors. The result is a silk that retains the beneficial properties of spider silk—such as high tensile strength and flexibility—while being produced on a scale that is commercially viable.

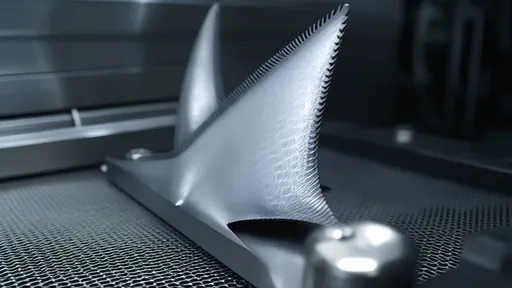

One of the most promising applications of this transgenic silk is in the field of sutures and surgical meshes. Traditional sutures, often made from materials like nylon or polyester, can cause inflammation or be rejected by the body. In contrast, spider silk proteins are biocompatible, meaning they do not trigger an immune response. This makes them ideal for closing wounds, especially in sensitive areas like the eyes or nervous system. Surgical meshes used in hernia repairs or tissue reinforcement can also benefit from this material's strength and biodegradability. Unlike synthetic meshes that may erode or cause chronic pain, spider silk-based meshes provide support while gradually being absorbed by the body, reducing the risk of long-term complications.

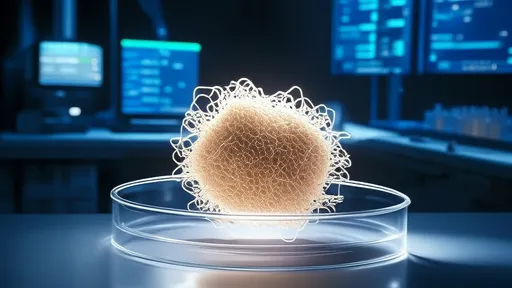

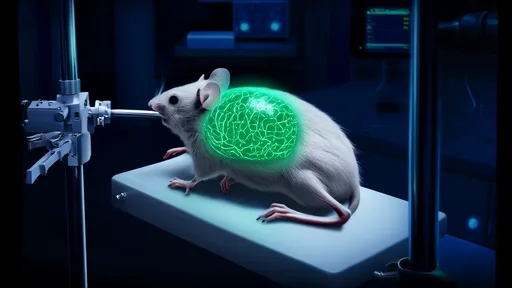

Beyond sutures, this material shows immense potential in tissue engineering. Scientists are exploring its use as scaffolds for growing tissues such as skin, cartilage, and even nerves. The silk's fibrous structure mimics the natural extracellular matrix, providing a framework that encourages cell attachment and growth. What sets it apart is its ability to be engineered with specific properties; for instance, by adjusting the genetic code, researchers can create silk that degrades at a predetermined rate or releases growth factors to accelerate healing. In experiments, nerve guidance conduits made from this silk have successfully helped regenerate damaged nerves in animal models, offering hope for future treatments of spinal cord injuries.

Another exciting frontier is drug delivery. The silk's protein-based structure can be modified to encapsulate pharmaceuticals, protecting them from degradation and controlling their release over time. This is particularly valuable for drugs that require steady, prolonged delivery, such as chemotherapeutics or hormones. Early-stage research has demonstrated that silk-based nanoparticles can target cancer cells with high precision, minimizing side effects on healthy tissues. The biodegradability of silk ensures that these delivery systems break down into harmless amino acids, leaving no toxic residues behind.

Despite these advancements, the path to widespread clinical adoption is not without hurdles. Regulatory approval for genetically modified materials is stringent, requiring extensive testing to ensure safety and efficacy. Scaling up production to meet global demand also presents logistical challenges, as it involves maintaining large populations of transgenic silkworms under controlled conditions. Moreover, public perception of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) remains a barrier in some regions, necessitating transparent communication about the benefits and safeguards of this technology.

Looking ahead, the convergence of biotechnology and materials science promises even greater innovations. Researchers are already working on enhancing the silk's properties further, such as by incorporating antimicrobial peptides or conductive elements for use in bioelectronics. As these developments unfold, transgenic silkworm silk could become a cornerstone of personalized medicine, where implants and therapies are tailored to individual patients' genetic profiles.

In summary, the fusion of spider and silkworm genetics has given rise to a material that transcends its ancient origins. From sutures that heal without scars to scaffolds that rebuild damaged tissues, this silk is poised to revolutionize medical practice. While challenges remain, the progress thus far underscores a broader trend: nature's designs, when harnessed responsibly through technology, can yield solutions that are both elegant and transformative. The story of spider silk in medicine is still being woven, but its threads are already strengthening the fabric of healthcare.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025