The horizon stretches in an unbroken line of deep blue, meeting a sky of equal intensity. For centuries, this vast expanse of ocean has represented both the sublime beauty and untamable power of nature. But now, in laboratories and on research vessels, scientists are developing a controversial technology that seeks to subtly alter this very view. Known as Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB), this geoengineering proposal is not about conquering the seas, but about collaborating with their existing systems to combat a global threat. It is a concept born of desperation and ingenuity, a potential tool in the climate solutions toolbox that is as audacious as it is simple in theory.

The core principle behind the Marine Cloud Brightening project is a phenomenon we observe every day: clouds. White, puffy clouds are highly reflective; they bounce a significant amount of the sun's incoming solar radiation back into space, creating a cooling effect. The albedo, or reflectivity, of a cloud is determined largely by the number and size of the water droplets within it. A cloud with a greater number of smaller droplets has a higher surface area and is therefore brighter and more reflective than a cloud with fewer, larger droplets. This is where the second part of the equation comes in: sea salt aerosol.

Over the open ocean, clouds naturally form around microscopic particles released into the atmosphere. These particles, known as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), include dust, pollution, and—most relevantly—tiny crystals of sea salt from ocean spray. The MCB plan proposes to enhance this natural process through a carefully controlled technological intervention. The vision involves a fleet of unmanned, wind-powered vessels autonomously cruising specific ocean regions. These vessels would be equipped with specially designed nozzles that use a process of ultrafine atomization to spray a mist of seawater into the air.

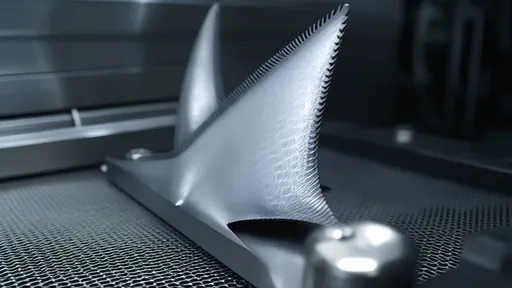

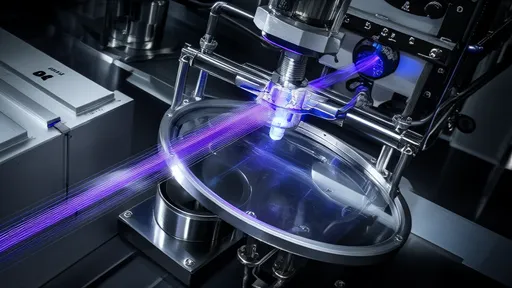

This is not a deluge of water, but a precise emission of billions of minuscule sea salt particles. The engineering challenge is immense—creating droplets that are just the right size (typically between 30 and 100 nanometers) to efficiently float into the lower atmosphere and act as additional CCN. As these engineered salt particles rise into the marine boundary layer, they become the seeds around which atmospheric water vapor condenses. The result, in theory, is the formation of clouds that are denser, whiter, and more persistent than would occur naturally, effectively creating a larger, more effective sunshade over a specific area of ocean.

The potential impact of such a scheme is what drives the research. By increasing the albedo of these extensive marine cloud covers, particularly over subtropical regions where stratocumulus clouds are prevalent, scientists project they could offset a portion of the planetary warming caused by greenhouse gases. Computer models suggest that a relatively modest increase in cloud droplet concentration over large oceanic areas could produce a significant cooling effect, potentially buying crucial time for the slower processes of decarbonization and carbon drawdown to take effect. It is framed not as a silver bullet, but as a possible temporary brake on the worst impacts of climate change.

However, the path from laboratory model to real-world application is fraught with profound scientific and ethical questions. The central scientific uncertainty lies in the non-linear and incredibly complex nature of cloud systems and atmospheric circulation. Artificially brightening clouds in one region could inadvertently alter precipitation patterns thousands of miles away, potentially causing droughts in one area and floods in another. The effect on marine ecosystems is another giant question mark. Would altering the amount of sunlight reaching the phytoplankton—the foundation of the marine food web—have catastrophic consequences, or would the mitigation of ocean heating and acidification from reduced atmospheric CO2 pressure be a net benefit?

Beyond the physical science lies a thicket of ethical and governance dilemmas. Who gets to decide to deploy such a planet-altering technology? Who would control the thermostat? The potential for geopolitical conflict is staggering. If a country or a corporation were to unilaterally begin a cloud-brightening program that subsequently disrupted the monsoon season in South Asia, the consequences could be dire. The concept of "solar geoengineering" is so potent that it often triggers discussions of a global governance framework, a set of international rules and oversight mechanisms that do not currently exist. The fear of a "moral hazard" is also prevalent—the concern that even discussing such a technological fix might reduce the political and societal urgency to cut emissions at their source.

Proponents of the research are quick to clarify its purpose. They argue that to make an informed decision about whether to ever use MCB, we must first understand it thoroughly. The current research is not about deployment; it is about investigation. Small-scale, controlled field experiments are designed to test the nozzle technology, study the microphysical processes of aerosol-cloud interactions, and refine the computer models that predict larger-scale impacts. This knowledge, they contend, is essential. If climate change accelerates into a series of catastrophic tipping points, the world may demand to know what all its options are. Having the research done transparently and within a robust ethical framework now is preferable to a panicked, poorly understood deployment later.

The Marine Cloud Brightening project sits at a difficult crossroads, a symbol of the immense challenges of the Anthropocene. It is a testament to human creativity in the face of a crisis largely of our own making, yet it also embodies the potential for unintended consequences on a planetary scale. It forces a conversation that extends far beyond atmospheric science into the realms of ethics, international law, and global equity. As the research continues, slowly and cautiously, it serves as a stark reminder of the profound responsibility that comes with the power to intentionally alter our planet's systems. The ultimate question is not just whether we can brighten the clouds, but whether we should, and under what conditions humanity would ever dare to take that step.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025