In the hushed halls of museums and research institutions, a quiet revolution is unfolding. For centuries, the internal secrets of priceless archaeological artifacts remained locked away, protected by their very value, which made destructive testing unthinkable. Conservators and archaeologists were often forced to rely on surface examinations, historical records, and guesswork to understand an object's construction, history, and integrity. The advent of X-ray imaging provided a significant leap forward, offering a glimpse beneath the surface. However, for many materials, particularly those with high density or compositionally similar elements, X-rays reach their limits, leaving a blurred, incomplete picture. Now, a powerful and elegant technique is emerging from the world of particle physics to shatter these limitations: neutron holographic imaging.

The fundamental difference between neutron and X-ray imaging lies in their interaction with matter. X-rays interact with the electron cloud surrounding an atom. Consequently, dense materials like metals absorb or scatter most X-rays, making it difficult to see details within a thick metal object or to distinguish between different heavy elements. Neutrons, being neutral particles, interact instead with the nuclei of atoms. This interaction is unique and not directly correlated with atomic weight. Some very light elements, such as hydrogen, carbon, and lithium, are highly visible to neutrons, while some heavy metals can be surprisingly transparent. This property makes neutron imaging exceptionally well-suited for archaeological applications. It can, for example, peer inside a solid bronze vessel to see clay core remnants or inscription plugs, or visualize the organic residues inside a sealed ceramic pot, all completely non-invasively.

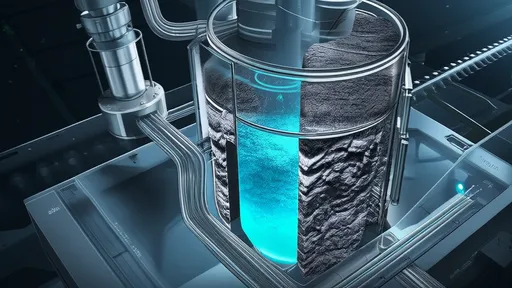

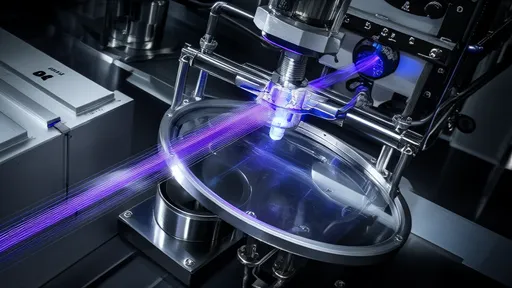

Traditional neutron radiography, much like a medical X-ray, produces a two-dimensional shadowgraph. While useful, it compresses all internal information into a single image, making it difficult to discern depth, separate overlapping features, and fully understand the three-dimensional structure of an object. Neutron holographic imaging, a more advanced application of neutron tomography, overcomes this. The process involves placing the artifact in the path of a collimated beam of neutrons, typically generated by a research reactor or a spallation source. A high-resolution digital detector captures the neutrons that pass through the object from hundreds of different angles as the object is meticulously rotated. Each of these 2D projections is a record of how the neutron beam was attenuated by the internal structure of the artifact from that specific viewpoint.

The true magic happens in the computational phase. Sophisticated reconstruction algorithms, most commonly a filtered back-projection method, process this vast dataset of 2D projections. The algorithm works by mathematically tracing the path of the neutrons back through the virtual space of the object. It effectively determines the points in three-dimensional space from which the detected neutrons originated, building up a voxel-by-voxel (3D pixel) map of the object's internal attenuation coefficients. The result is a precise, navigable, three-dimensional digital model of the artifact's interior. Researchers can digitally slice through this model in any plane, isolate specific components, measure internal dimensions, and visualize hidden features with astonishing clarity, all without ever touching a scalpel or a drill.

The applications of this technology in archaeology and cultural heritage are profound and are already yielding groundbreaking discoveries. In one landmark study, a seemingly unremarkable medieval composite reliquary statue, long assumed to be solid, was examined with neutron holography. The scan revealed a complex internal cavity containing not only fragments of bone and cloth, confirming its function as a reliquary, but also a small, tightly scrolled parchment document that had been completely unknown. The non-metallic ink on the parchment was invisible to X-rays but was clearly delineated by the neutrons, offering a potential treasure trove of historical information waiting to be deciphered.

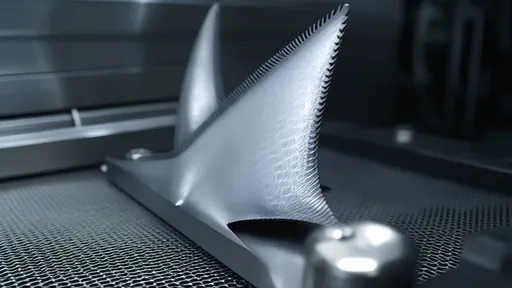

Metallurgy is another field reaping immense benefits. The study of ancient weapons, tools, and jewelry often hinges on understanding their manufacture—such as casting techniques, joining methods, and the presence of repairs or flaws. Neutron holography can reveal internal voids left by gas bubbles during casting, the precise morphology of solder joints invisible from the outside, and even the differential corrosion patterns that threaten an object's stability. For instance, scanning a prized ancient sword can show the integrity of the tang hidden within the hilt, reveal modern repairs, and map the extent of corrosive cracking, providing crucial data for its conservation.

Perhaps one of the most exciting potentials lies in the analysis of closed vessels. Ceramic amphorae, unguentaria, and other sealed containers often hold the residues of their original contents—oils, wines, perfumes, or medicines. Neutrons are particularly sensitive to the hydrogen in these organic residues. Holographic imaging can map the distribution and volume of these residues along the inner walls and base of the vessel, even if it is still sealed with its original stopper. This provides archaeologists with direct chemical evidence of trade, diet, and cultural practices without the need to break the object open, preserving its integrity for future generations.

Despite its incredible potential, neutron holographic imaging is not without its challenges and limitations. Access is the primary hurdle. The requirement for a neutron source means that research is confined to a limited number of large-scale national and international facilities, such as the Institut Laue-Langevin in France or the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source in the UK. The process of scheduling "beam time" is highly competitive, and transporting priceless, often fragile, artifacts to these facilities requires meticulous planning and security. Furthermore, the act of irradiation itself, while almost always non-damaging, must be carefully considered for each unique material type. For most stable inorganic materials—ceramics, stone, metals—the neutron dose poses no risk. However, for certain organic materials or artifacts with very sensitive coloration, pre-studies are conducted to ensure complete safety.

The future of this technology is bright and points toward greater accessibility and resolution. Efforts are underway to develop compact, accelerator-based neutron sources that could one day be installed in major museums or research universities, drastically reducing the access barrier. Advances in detector technology continue to improve spatial resolution, allowing for the visualization of ever-finer details. Furthermore, the development of energy-resolved or polarized neutron imaging adds another dimension of information, potentially allowing for the mapping of internal stresses in metals or the identification of specific crystalline phases within ceramics and minerals.

In conclusion, neutron holographic imaging represents a paradigm shift in archaeological science. It fulfills the conservator's ultimate dream: the ability to see the unseen without causing harm. By providing an unambiguous, three-dimensional window into the hidden hearts of ancient objects, it is transforming our understanding of history, technology, and artistry. It allows us to ask questions that were previously impossible to answer and to preserve the full context of an artifact—both its external beauty and its internal story—for centuries to come. As this technology continues to evolve and become more accessible, it promises to become an indispensable tool, ensuring that the deepest secrets of our past are finally brought to light.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025