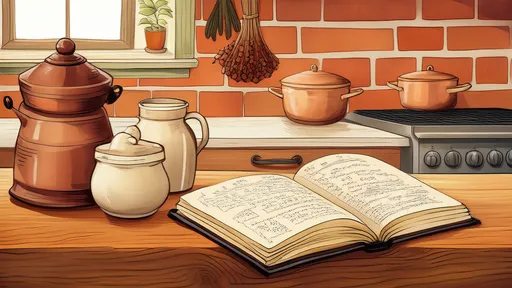

The art of breadmaking transcends mere recipes and measurements, residing instead in the subtle language of touch and texture that speaks through the dough itself. For centuries, bakers have relied not on timers or thermometers, but on their hands to gauge the most critical phase of fermentation. This tactile wisdom, passed down through generations, remains the true soul of craftsmanship in baking.

To understand dough through touch is to engage in a silent dialogue with living organisms. Yeast and bacteria work tirelessly, transforming flour and water into a complex ecosystem of gases and organic acids. The baker’s hands become calibrated instruments, sensitive to the slightest changes in resilience, elasticity, and airiness. This is not a skill learned overnight, but a sensory education developed through patience and attentive repetition.

Begin with a freshly mixed dough. In its initial state, it often feels dense, shaggy, and uneven. Your fingers will detect resistance, a certain stubbornness in the mass. As the first folds are incorporated during the initial kneading or stretch-and-fold cycles, the texture begins to change. It becomes smoother, more cohesive. The proteins align, forming the gluten network that will eventually trap the gases produced during fermentation.

The first critical checkpoint arrives after the bulk fermentation has begun. Gently press a floured finger into the top of the dough. In very young dough, the indentation will not hold. It will spring back immediately, like a firm memory foam pillow, indicating that the gluten is still tight and the yeast has not produced enough carbon dioxide to create significant aeration. The dough feels strong and eager, but under-fermented.

As time progresses, the same test will yield a different result. The ideal window for many breads is when the dough offers a slight resistance to the poke but the indentation remains partially filled. It should spring back slowly, leaving a shallow ghost of your fingerprint. This is the sweet spot—the dough is alive, gassy, and elastic, but has not yet exhausted its food supply or become overly acidic. It feels alive, buoyant, and full of potential.

An over-fermented dough tells a sad tale through touch. A poke will cause the surface to deflate slightly, and the indentation will not spring back at all. The dough feels weak, slack, and lifeless. It may have a sticky, wet quality on the surface, even if you didn’t add excess water. It has lost its structural integrity; the gluten network has been degraded by prolonged enzymatic activity. Baking it will result in a flat, dense loaf with muted flavor.

Beyond the poke test, the entire handling of the dough informs the baker. During pre-shaping and shaping, well-fermented dough has a particular quality. It is billowy and light, yet strong enough to hold a smooth, taut surface when shaped. It doesn’t fight you, but it doesn’t collapse either. It feels like handling a cloud with structure—a delightful, airy mass that obeys your command without being rigid.

In contrast, under-fermented dough is difficult to shape. It is tight and springs back aggressively, fighting against being formed into a loaf or boule. It lacks the extensibility that proper fermentation provides. Over-fermented dough is the opposite; it offers no resistance whatsoever. It spreads like a puddle, unable to hold any shape you try to give it, feeling limp and exhausted.

The temperature of your hands is another subtle clue. A actively fermenting dough will feel slightly warmer than the ambient air in the room, a testament to the metabolic activity of the yeast producing heat. A dough that has finished fermenting or is slowing down may feel closer to room temperature. This thermal cue, while subtle, adds another layer to the tactile assessment.

Learning this language requires baking the same loaf repeatedly. Note how the dough felt at different stages, and then correlate that feeling with the outcome of the baked bread. Did it feel strong and springy, but then bake up with a tight crumb? It was likely under-fermented. Did it feel slack and sticky and bake into a flat pancake? It was over-fermented. This feedback loop is your greatest teacher.

Eventually, you will move beyond the conscious poke test. You will know the fermentation is complete simply by lifting the tub or touching the side of the bowl. The dough will jiggle with a specific, quivering lightness. It will feel airy and delicate, yet cohesive. This deep, intuitive knowledge is the ultimate goal—where your hands and the dough communicate without need for conscious thought.

Embrace the variations. Different flours, hydration levels, and ambient temperatures will change how the dough feels. A high-hydration dough will always feel more slack and sticky than a stiff, low-hydration dough, even at perfect fermentation. Whole grain flours absorb more water and can feel drier, yet ferment faster. Your hands must learn these dialects of the same language.

This tactile approach connects you to the oldest traditions of baking. It is a rejection of industrialized, clock-dependent baking in favor of a responsive, sensory practice. The dough will tell you when it is ready; you need only learn to listen with your hands.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025