There is something profoundly intimate about the way food connects us to our past. The scent of a particular spice, the texture of a dough, the first taste of a long-forgotten dish—these sensations can instantly transport us back to a grandmother’s kitchen, to a time and place steeped in memory and love. Preserving and recreating these culinary heirlooms is more than a hobby; it is an act of devotion, a tangible link to our heritage. It is the art of ensuring that a beloved flavor does not vanish with the passing of a generation.

The journey begins not in the kitchen, but at the table. Before you even think about preheating the oven, your most crucial tool is a notebook and a pen, or perhaps a voice recorder. The goal is to capture the recipe not as a sterile list of ingredients and steps, but as a living narrative. Sit down with your grandmother, if you are fortunate enough to have the opportunity. Do not rush. Let her tell you the story behind the dish. Ask her not just "how much," but "why." Why that specific brand of vanilla? Why room-temperature butter? Why a pinch of sugar in the tomato sauce? These are the nuances that transform a generic instruction into her instruction.

Pay close attention to the language she uses. Family recipes are rarely documented with scientific precision. They are a lexicon of feel and experience. You will encounter instructions like "a coffee mug of flour," "a knob of butter," or "bake until it smells done." These are not frustrating vagaries to be corrected; they are the heart of the recipe. Your mission is to decode this language. "A coffee mug" likely refers to a specific mug that always sat by her pot. "A knob" is probably the amount she could pinch off a stick of butter with her fingers. "Until it smells done" is a sensory checkpoint tied to the Maillard reaction and the caramelization of sugars, something she learned to recognize through decades of repetition.

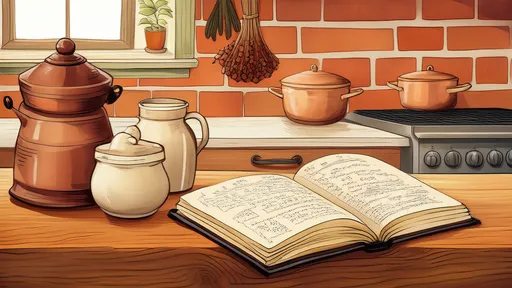

If a direct conversation is not possible, turn to other relatives, old photo albums, or handwritten notes. Often, the most cherished recipes are found on stained, fraying index cards or in the margins of cookbooks. The stains themselves are data—a splatter of oil marks the page for the frying step, a smudge of chocolate indicates the point where you mix in the chips. These physical artifacts are priceless clues. Transcribe them exactly as written, preserving the original phrasing and any idiosyncratic spelling or abbreviations. This is your primary source material.

With your gathered intelligence, the next phase is experimental archaeology in the kitchen. Your first attempt should be a faithful reproduction, following the decoded instructions as closely as possible. Do not make substitutions or "improvements." The objective is to establish a baseline, to understand the dish as it was originally made. Weigh and measure everything, even the imprecise "handfuls." Note the exact weight that particular handful of grated cheese turns out to be. This process of quantification is vital for consistency later, but it must first be rooted in the authentic, imperfect original.

Taste is the ultimate judge, but it is a flawed and subjective one. Our palates change over time, and nostalgia can cast a powerful, distorting glow. Whenever possible, have your grandmother taste your first attempt. Her feedback is gold. Does it need more salt? Is the texture right? Was the pan not hot enough? This collaborative tasting and adjusting is where the true magic of recreation happens. It is a dialogue across generations.

Beyond the recipe itself, consider the entire ecosystem of the meal. What else was served alongside this dish? Was it a Sunday supper or a holiday feast? What was the atmosphere? Recreating the context can profoundly enhance the experience of the food. Playing the music she listened to, using her serving platter, or setting the table with her china can complete the sensory journey, making the first bite taste even more "right."

Finally, the work of preservation. Once you have successfully recreated the dish and standardized the measurements without losing its soul, document it thoroughly. Write a new recipe card that includes both the precise measurements (e.g., 250 grams of flour) and the original familial instructions ("or about two of Grandma's coffee mugs"). Take photographs of the process and the finished product. Consider making a video of your grandmother preparing the dish, capturing her techniques—the way she rolls dough, folds egg whites, or tests a cake with a toothpick. These multimedia records are the best defense against the erosion of time.

This endeavor is a labor of love. It requires patience, curiosity, and a deep respect for the craft of those who came before us. There will be failed batches and moments of frustration, but the reward is immense. It is the ability to summon a beloved presence, to hear a story in the sizzle of onions in a pan, and to guarantee that the flavors of love and care continue to nourish generations yet to come. You are not just saving a recipe; you are keeping a story alive, one delicious bite at a time.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025